Feb 6, 2024 | Scholarly publishing

The ALPSP panel for this discussion on AI and the impact it is having within academic publishing was made up of Nicola Davies, IOP Publishing (Co-chair), Helene Stewart, Clarivate (Co-Chair), Meurig Gallagher, University of Birmingham (Speaker), Matt Hodgkinson, UKRIO (Speaker) and Jennifer Wright, CUP RI Manager (Speaker).

It was fascinating to see how the conversation around AI has moved on within a few months regarding this technological advancement. Institutions, publishers and journal stakeholders all have a concept of AI and are developing policies and guidance about how we should be using it and are underpinning the “what for?”.

Many of us by now will have tried asking a Large Language Model (LLM) to write a paragraph or create an image using Artificial Intelligence. It’s brilliant to watch how quickly tasks can be created, large blocks of text are generated at an immense speed, and right before us we see how quickly human intelligence can be mimicked. This notion was highlighted in Meurig Gallagher’s presentation; that essentially AI is trying to act as human as possible using the instructions it has been provided with. However, when these tools are posed with mathematical equations it does not have the knowledge to apply the learning and therefore can spectacularly fail! These “gaps” therefore build into the guidance stakeholders need to be aware of when creating policy around AI – it cannot be relied upon solely to do the work. Matt Hodgkinson developed this further and shared many caveats that researchers and general users might come up against when using chatbots:

- Many LLMs are unvalidated for scholarly uses.

- References should be fact-checked as they can be falsified, therefore it is important to check sources and supporting literature.

- The quality of evidence is not assured.

- Outputs may be based on using out-of-date information based on “old” training material.

The ominous but noteworthy warning was circulated that “if you are not an expert, you will be fooled by fluent but incorrect outputs”. Therefore, all of us involved in scholarly publishing need to be mindful of these contributions and check author statements within articles to assess whether an LLM has been used. Of course, one of the largest threats we are witnessing is the output of paper mills and their use of AI could lead to the tool’s collapse as its knowledge bank is infiltrated with “fake” data, which if left undetected will pollute the pool where the data is extracted from.

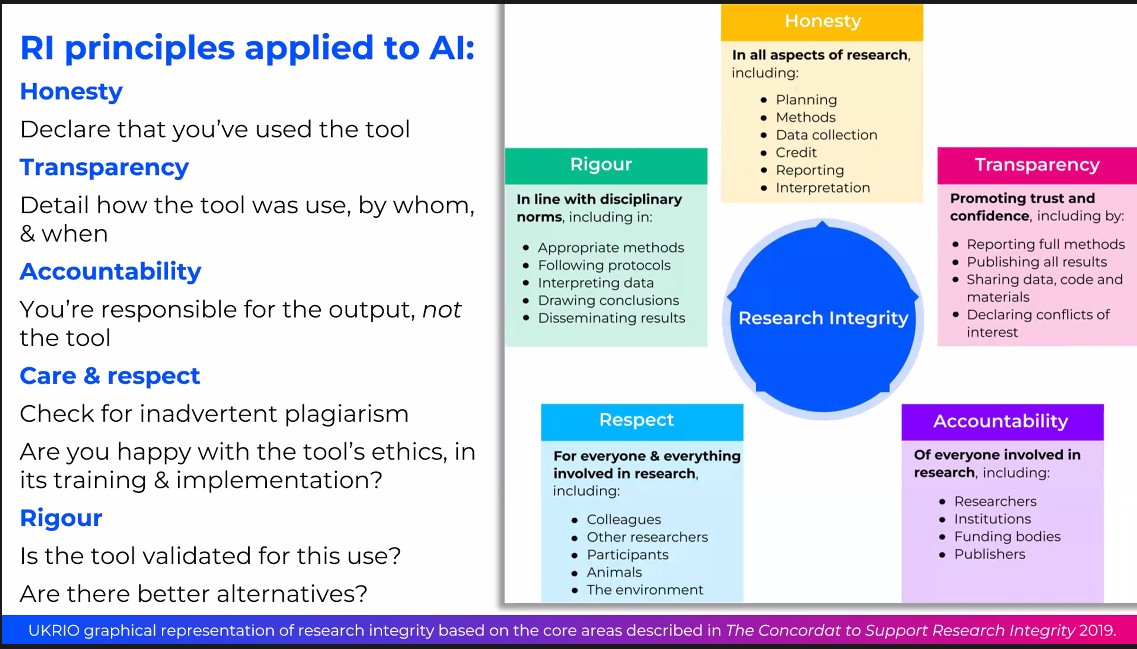

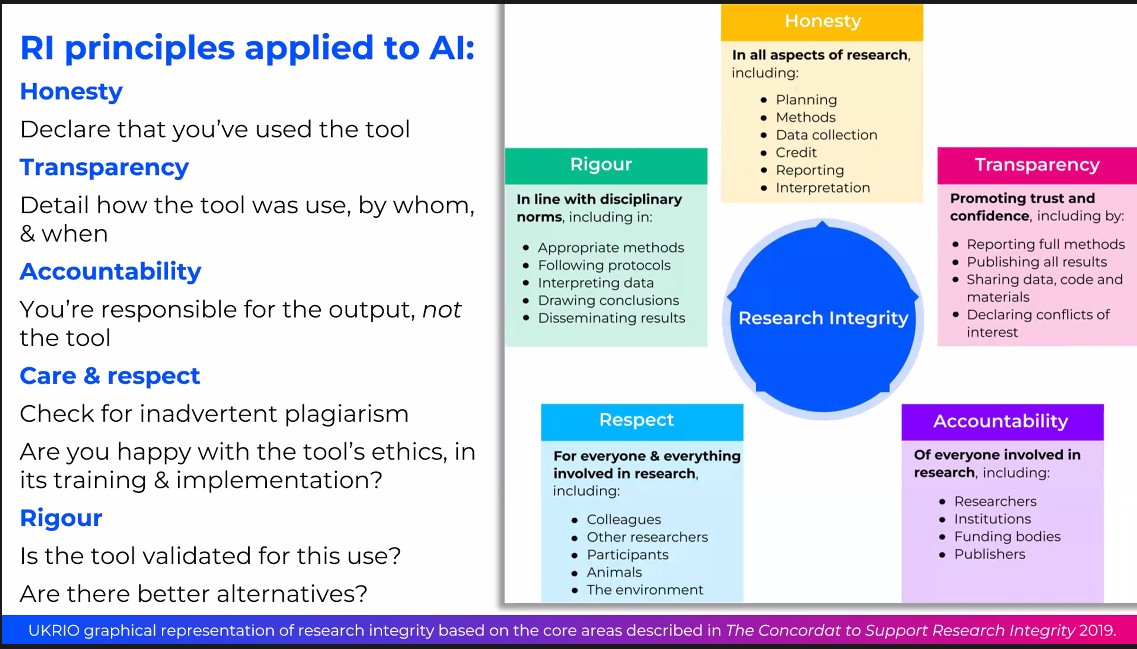

Nonetheless the principles of Research Integrity can be applied to the use of AI-generated content and Matt shared this slide to disclose how these principles are applied:

UKRIO presentation at ALPSP 2024

Dr Jennifer Wright from Cambridge University Press shared with the audience how to implement transparency which is really the crux of what many VEOs are looking at. It was suggested that AI declarations should be included within image captions, acknowledgements, and methodologies if applicable and the details that should be shared include the type of model that was used, eg: CHATGPT, and how and when it was accessed. It is also important to include any additional COI statements because of the use of the model. Looking forwards, Dr Wright elaborated on future considerations and posed some important questions around reporting standards: What will the impact be of AI on the scholarly record? How could/should/will research and publication practices change? How will concepts such as retractions be enforced? Can a bot retrain itself?

The challenges are still clearly evident with AI. However the more we progress and understand how it can be used, trust markers can be identified to validate the outputs. As long as scholars use and do not abuse the tech, we could watch something incredible unfold!

Dec 2, 2023 | Scholarly publishing

AI is inevitably going to infiltrate all our lives in some way or another in the near future; learning how we shop, communicate, write, create and plan our lives. We therefore also need to look at adapting our ways of working to benefit from these technological advancements. Working alongside this adaptive new tech, and generating new guidance and principles, will enable us to harness and nurture it. We can create preventative methods to stop bad actors abusing and infiltrating the systems we have in place to educate and teach.

At the NEC Annual Publishing Conference (7 November 2023, London), the keynote was delivered by David Smith from the IET who looked “Back to the Future!”; highlighting the importance of an article published by Darcy DiNucci. Fragmented Futures (published in print, 53.4, 1999) demonstrates technological growth and that the Web she wrote about was only the beginning…how things have changed in 20 years! Essentially it is thought we are at a similar point with AI; it is new, raw and ready to be refined and developed.

Leslie Lansmann, Global Permissions Manager from Springer Nature, discussed how Large Language Models (LLM) such as ChatGPT are ingesting content, and this is not yet fully disclosed by AI companies. This is important to monitor as we must maintain the stewardship for the content and protect copyright and protected manuscripts. As much as AI is currently learning – it probes and reiterates content – it does not understand the deeper context behind the language. The publishing industry is however having to react to the developments in technologies, many publishers are imposing bans on AI content, and introducing new and different policies.

The discussion around authorship is constantly developing and debated – should research be done using AI? Can it help an author whose first language isn’t English produce a more succinct piece of work? If the data is accurate and the same research principles are adhered to, maybe we should move towards incorporating it into our practices. This notion was delivered by Anastasia Toynbee from the Royal Society of Chemistry who was looking at the problem of non-native English speakers and how these tools could help. The key feature of this was that a problem had been highlighted and AI was being used to support it – not the other way around.

It became clear from all the speakers how important it is to identify the problem initially and use AI tech/tools to help with it, rather than decide how to harness and squeeze new systems into processes that are working well. Ian Mulvany at BMJ really brought home this idea that we as an industry need to balance risk vs opportunity. AI has perception, however no intention to act; therefore we are in a position through governance, policy, and stewardship that we can lead AI to improve processes and not be reactive and in fear of the unknown! Andy Halliday , Product Manager at F100 iterated the benefits and pitfalls of AI and how humans can help harness this tech and enable it to support our ecosystem and develop a sense of AI preparedness.

We are in the awakening of AI. The box has been opened and we all have access to create new and exciting content, images and access information much easier than ever before. As the discussions continue it will be really exciting to see how developments are made, what fixes it can be used for, and how policy and guidance are updated to meet the demands of users.

Oct 16, 2023 | Scholarly publishing

Following the UKRIO workshop hosted by IOP Publishing and Karger on 20th September 2023, we discuss here the principles required for correcting academic literature and the key players responsible.

Post-publication correction notices are used to update or append research using neutral and factual terminology. Mistakes can be made, and post-publication corrections are not used to punish authors/journals. Corrections are not always a fault with the research, it could be an honest error.

Notices should follow industry standards and include key elements, such as: DOI, title, volume/issue number, year of publication and a description of the error and any actions taken to remedy the research.

The original article is not usually updated; however, it can be amended if it warrants legal or privacy concerns. This decision will be in accordance with the publisher’s policy and best practice. For example, a health journal may update drug doses if it would impinge upon patient care – this would be outlined in the notice and the content updated. The aim is to be transparent in the notice and include bi-directional linking. The notice should appear online and in print.

Types of Notice

- Corrigendum. Usually an error introduced by an author.

- Erratum. Usually an error introduced by the publisher.

- Retraction. The most serious type of notice, following a full investigation.

- Publisher’s note. Used to notify that an error may be in the content/under investigation.

- Expression of concern. Advising the reader that there might be errors or untrustworthy content.

Withdrawal

Best practice is not to erase the content – a withdrawal notice, which is deemed the most serious type of correction, means that the DOI remains but the PDF is removed, not to cause detriment to the scholarly work.

Myths and Barriers to Correcting the Scholarly Record

Myths

- A correction does not always mean there is something ‘wrong’ with the research.

- A publisher’s responsibility for their content does not stop at the publication.

- An author doesn’t want to hear if you spot a potential error in their research.

Correcting the record

- Errors happen! Correcting the record needs destigmatising and normalising through education and transparent communication.

- Publishers must be willing to correct inaccuracies transparently with the support of all parties involved in the research ecosystem.

- Researchers should be willing to receive communications about their publications. Comments should be neutral and non-accusatory.

Standards are set by multiple bodies, including ICMJE, COPE, STM, and PubMed, which form a basis of recommended principles. Published content is a snapshot in time and should not be updated to reflect recent events/changes (for example, affiliation updates).

Who Decides What Needs to be Corrected?

This should be done in a partnership which can include the publisher, author, editor and editorial teams, depending on the query. For example, a plagiarism investigation will require more input from all involved as opposed to a typographical error in a name. Accuracy of publications must be maintained by all members within the ecosystem to uphold the scholarly record, which includes publishers, authors, readers, reviewers, editors and research institutions.

Publishers

- Need to have checks and balances in place to avoid inaccuracies being published.

- Correct inaccurate content in a thorough and timely manner using transparent language.

- Investigate concerns brought to the journal regarding the accuracy of content.

Authors

- Have a responsibility to avoid errors being introduced – thoroughly checking the content at pre-publication checks.

- Inform the publisher of any inaccuracies they identify in their own work.

- Inform co-authors of any inaccuracies discovered, whether accidental or intentional.

- Cooperate with investigations into concerns about accuracy of publications.

Readers

- Have a responsibility to report suspected errors in publications – this should be done neutrally to a body with responsibility for accuracy of the publication.

Reviewers

- Have a responsibility to review a manuscript critically and provide a succinct review. They should also report concerns with content to a appropriate body who has responsibility for accuracy regarding the publication.

Editors

- Have a responsibility to critically analyse manuscripts and report suspected errors.

- Investigate errors brought to their attention.

- Collaborate with the journal or publisher whilst an investigation is pending, bringing their subject expertise.

Research Institutions

- Have a responsibility to promote responsible research through education and foster a transparent research culture.

- Required to have a mechanism for reporting and investigating potential.

- Report the outcomes of the investigations to the publisher affected.

What is the Impact of Correcting Content?

It is important to correct and not remove content. Corrections will always be a customary part of maintaining the scholarly record and should only be done if necessary. Removing or editing content could impact a researcher’s career. Retractions are the most serious type of notice that can be issued and can have a serious impact on the career of a researcher. Indexing services can be impacted, by splitting citations. Incorrect indexing can cause issues for journals, authors and publishers. Google Scholar scrolls every 6 months and therefore it does take time for services to be updated regarding notices such as retractions and withdrawals. Publishers must be responsible with post-publications to prevent inaccuracies in the scholarly record.

Sep 22, 2023 | Scholarly publishing

On the 7th September 2023, the COPE Forum took place, discussing peer review models and examining the current threats to the systems and challenges faced by all parties involved.

Peer review has long been the cornerstone of scholarly publishing, serving as a quality control mechanism to ensure the accuracy and integrity of research. This communal effort involves authors, editors, publishers, and reviewers working together to uphold the standards of academic discourse. However, the peer-review process is facing unprecedented challenges that threaten its effectiveness. Here, we will discuss the importance of peer review, the emerging challenges it faces, and potential solutions to fortify this vital system.

Peer Review

Peer review plays a pivotal role in maintaining the credibility and trustworthiness of scholarly publications. Its benefits include:

- Quality Assurance: Peer review helps identify errors, flaws, and biases in research, ensuring that only high-quality and reliable studies are published.

- Validation of Findings: It serves as a validation mechanism, confirming the authenticity and significance of research findings.

- Feedback for Improvement: Reviewer feedback provides authors with valuable insights for improving their work.

- Conflict Resolution: Peer review resolves conflicts and disputes regarding research claims and methodology.

Challenges Facing Peer Review

Despite its essential role, the peer-review process is facing several challenges:

- Shortage of Skilled Reviewers: There is a growing scarcity of qualified reviewers willing to dedicate their time and expertise to the peer review process. This can lead to overburdened reviewers and delays in publishing.

- Fraud and Misconduct: Organized fraud, such as peer-review rings, fake papers, and manipulated results, threatens the integrity of peer review, undermining trust in scholarly publishing.

- AI and Large Language Models: The advent of AI tools and large language models has introduced new challenges, including the generation of convincing but false research papers and the potential automation of the peer-review process.

Solutions for Strengthening Peer Review

To address these challenges and preserve the integrity of peer review, several strategies can be considered:

- Reviewer Recognition and Training: Acknowledging and rewarding reviewers for their contributions can help motivate and retain skilled reviewers. Providing training and guidelines for reviewers can enhance the quality of their assessments.

- Transparency and Accountability: Journals can adopt transparent peer-review practices, such as open peer review or preprint reviews, to increase accountability and trust in the process.

- Technology and AI: Utilize AI tools not only to detect fraud but also to assist in the peer-review process. AI can help identify potential conflicts of interest, plagiarism, and statistical errors.

- Diversifying Reviewer Pools: Encourage diversity among reviewers in terms of gender, ethnicity, and geographical location to ensure a broader range of perspectives.

- Collaboration Among Stakeholders: Authors, editors, publishers, and reviewers should work together to establish and maintain best practices for peer review.

The peer-review process is at a critical juncture, facing challenges that threaten its efficacy and credibility. However, with concerted efforts from all stakeholders, including researchers, journals, and the broader academic community, it is possible to fortify peer review, adapt to the changing landscape, and ensure that scholarly publishing continues to uphold the highest standards of research integrity. Only through collective action can we safeguard the trust that underpins the dissemination of knowledge in academia.

Jul 14, 2023 | Company information and news, Scholarly publishing

Managing Editors, Administrators, Journal Staff, Editorial Assistants – whatever you want to call us, we play an integral role in getting your manuscript through peer review. But you may wonder what it is we actually do.

You see, we Managing Editors wear many hats. The honest answer to What It Is We Do is really that we do whatever our particular editor, publisher, and journal workflow needs us to do. But there are some tasks that are common for most of us, so here’s a quick TEH Blog rundown.

System support

Most journals these days make use of an online submission system. These systems are absolutely invaluable to the smooth running of a busy global journal (more on that here), but we are all too aware that they can be confusing and frustrating if you aren’t used to using them.

Your friendly neighbourhood Managing Editors are therefore on hand to answer any questions, resolve any upload problems, and generally support authors, reviewers, and editors in successfully navigating their way through all the buttons, links, and questions.

Administrator checks

Once you’ve submitted your manuscript (whether you needed our help do to so or not), the first thing that will happen is that somebody will check it over to make sure that nothing is missing, and that it’s suitable for peer review. And just who might that “somebody” be? You’ve guessed it: the Managing Editor.

The checks we’re asked to perform varies journal to journal. Sometimes it is literally a case of making sure the manuscript text hasn’t been missed out by mistake, and sometimes it’s an in-depth analysis of your referencing format. Whatever the checks are, it’ll be us who gets in touch to guide you through making any changes, and it’s us who will approve it for review.

Status updates

It might feel like you submitted your manuscript aaaages ago and the status in your author centre has been saying the same thing for a really long time… When the waiting game finally gets too much and you fire off an email to the journal’s Editorial Office, it’s one of us who will respond to give you some idea of what’s happening.

Unfortunately delays do happen – editors and reviewers are, after all, busy people and inevitably deadlines get missed periodically – but we are always working to keep them to a minimum, and are always happy to give you an update. You can find out more about what goes on behind the scenes here.

Point of contact

It’s not just status updates for authors that we handle, however. Been asked to review a paper but need an extension on the deadline? Drop us an email. Need to return your conflict of interest form for your accepted paper? Send it over to us. Somehow wound up with multiple accounts on the submission system that are causing you login problems? We can help with that, too.

In fact, pretty much anything you need as an author, reviewer or editor can be sent to us. If we’re unable to help you ourselves then we will know who to forward the message on to. We Managing Editors are your one-stop shop for all your peer review needs.

Reporting

One of the many benefits of peer review being handled through a submission system is that we can gather data on number of submissions, how many of those get accepted, and even where in the world the research originated from.

When you’re down in the trenches working away at getting the papers assigned to you through peer review it’s not always easy to see the bigger picture, so being able to get actual figures on how many submissions are coming into your journal (and, crucially, how that compares to how many submissions you’ve received in previous years) is absolutely invaluable.

And it’s we Managing Editors who can not only get you this data, but organise it into a report that makes sense of it all.

May 15, 2023 | Scholarly publishing

It seems like everybody’s talking about AI these days. No longer is it just the stuff of Sci-Fi movies, it’s fast becoming a part of our day-to-day lives – writing, painting, talking; you name it, there’s an AI app available to do the hard work for you. But what impact is this having on the world of scholarly publishing?

Chatbots as co-authors

We are already seeing instances of chatbots, such as ChatGPT, being listed as co-authors on academic papers submitted to journals. This is naturally problematic – can an AI really qualify as an author?

The general consensus amongst the publishing world, for the time being at least, is that no, they can’t. We Managing Editors are now often required to check for chatbot authorship at submission so we can ask that their “contribution” to the work be listed in the Acknowledgement section rather than being given co-author status.

More information on authorship can be found in our previous post on the authorship question.

Chatbots as ghost writers

The instances where chatbots are being listed as co-authors are one thing – we are at least being told that there was AI involvement in the writing of the paper. Far more troubling are instances where papers are being predominantly or entirely written by AI and being submitted as if they had been produced by humans.

The Committee on Publishing Ethics (COPE) says that “This has significant implications for research integrity, and the need for improved means and tools to detect fraudulent research. The advent of fake papers and the systematic manipulation of peer review by individuals and organisations has led editors and publishers to create measures to identify and address several of these fraudulent behaviours. However, the detection of fake papers remains difficult as tactics and tools continue to evolve on both sides.”

One of the problems of AI is that it doesn’t have a moral or ethical code, so has no qualms about falsifying data then convincingly analysing it. This is a huge concern when it comes to the next generation of “paper mills” – groups who produce academic-looking papers for profit alone. In their hands, AI could be incredibly damaging to research as it’s not always easy to spot.

For more from COPE, see their recent discussion on this topic.

So, what’s the future?

With AI becoming more and more part of our lives, it is quite plausible that academia will embrace a little electronic help when it comes to writing papers – academics and researchers are busy people so if AI helps to reduce their workload, then why would they not take advantage of that?

The question is really where do we draw the line, and, as this technology is so new to most of us, this is a very difficult question to answer. Certainly it needs to be clearly stated when AI has been used to generate some of the text, and how involved AI has been in generating the data on which the manuscript is based.

This is something that the publishing world is monitoring closely, with many discussions of the implications on research integrity being held. The industry is working to produce tools to help us detect when a seemingly regular paper produced by human hands may actually be nothing of the sort…