Jul 18, 2025 | Scholarly publishing

COPE Forum 2025: Ethics in the Age of AI

The COPE Forum on 1 July 2025 was a thought-provoking gathering. Dissecting the dilemmas AI brings to the editorial table, the forum spotlighted the evolving challenges – and possibilities – in publication ethics.

Hot Topic: Artificial Intelligence in Publishing

A major theme of the discussion revolved around how AI is reshaping scholarly publishing:

- Generative AI is influencing everything – from research paper drafting to figure creation and peer review.

- Concerns were raised around transparency, quality control, and the ethical boundaries of AI-driven content.

The growing consensus? AI is a collaborator, not a co-author. Most policies and guidelines reject AI tools like ChatGPT being listed as authors, however disclosure statements are encouraged to highlight if an AI tool has been used in the creation of the work.

Ethical Guidance from Key Organizations

COPE, along with STM, WAME and EASE, is developing frameworks to guide responsible AI use:

- Disclosure expectations: Authors must clearly acknowledge any AI assistance in manuscript preparation.

- Classifying AI use: A helpful chart distinguishes acceptable use (editing and formatting text) from questionable practices (generating data or results).

Editors, Reviewers & Publishers – Stay Human, Stay Honest

AI is showing promise in streamlining workflows for editors and reviewers. Largely with a focus on using AI tools for checking the clarity and quality of language use and to support reference checks within manuscripts.

However, reviewers and editors must validate all content themselves. Uploading confidential papers into AI tools could breach trust and privacy and compromise the Publisher by sharing third party data.

The LOCAD Framework: Vetting AI Tools

Before using any AI tool, it is advisable to apply the LOCAD test:

- Limitations: Know the tool’s scope.

- Ownership: Understand rights over the content it generates.

- Confidentiality: Protect sensitive data.

- Accuracy: Validate the information.

- Disclosure: Be upfront about usage.

Final Thoughts: The Future Is Collaborative

The forum concluded on a hopeful note:

“AI should work with us, not instead of us.”

Ethical governance, responsible use, and human creativity must remain the core of scholarly publishing – even as AI becomes a more integrated partner in the process.

Feb 13, 2025 | Scholarly publishing

Guest post by Michael Upshall, reposted with his permission.

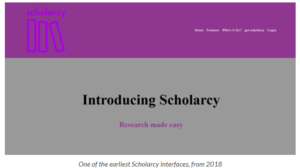

Phil Gooch, founder of the successful startup Scholarcy, was the highlight of the first-ever AI, Publishing and EdTech Meetup (London, February 2025). Each of the four speakers was allotted 15 minutes, and Phil’s talk was the only one not to include any slides and the only one that was, as he mentioned, a real story. Scholarcy, founded by him and Emma Warren-Jones in 2018, was sold in 2024 to Texthelp, a leading provider of scholarly support tools for higher education. It was, and is, one of the best tools to make use of AI to assist the scholarly research process.

Roughly restated (this was not an event for detailed notes), his nine principles are:

- Something you care about. If you are going to spend all your waking hours on a new business, make sure it is something you really care about. In Phil’s case, it arose from his own PhD study, looking for a better way to summarize and to manage his literature review, rather than using highlighters and PDFs.

- Find a cofounder, with complementary skills. Phil could build tools; Emma could do marketing.

- Be prepared to pivot. Scholarcy’s initial market was selling services to publishers, but this was not sustainable. They switched to selling direct to users, and, fortunately, they had already built an engine, so they only needed a front end. Their second, and equally big pivot, was the discovery that the tools they provide for any student or researcher were equally beneficial for neurodivergent learners, which meant they were able to sell their product in markets where some funding was available.

- Be frugal at the start. They were fortunate to get a small investment, but this was not one of those startups that raises £20m and then burns the lot. In their first year, their total income was £140 – fortunately, the founders were working part-time at this point.

- Create a team. You need a team, and the best recruits are people who come to you. A would-be designer presented them with an entire site redesign, free of charge, and they offered him a job.

- Branding. The next step was to integrate the website and marketing initiatives in a single theme.

- Automation. Make sure you automate your process as soon as possible.

- Organic growth (this applies to a B2C company). They found an SEO guru to get them to the top of the search rankings, and identified new would-be influencers who were mentioning the product without payment.

- Spread the risk. For some years the whole operation was run from a card payment account, rather than a business bank account, which meant the entire business ground to a halt when they once became overdrawn.

Phil gave a remarkably frank and engaging presentation of what it was like to create and to grow a startup – right up to the moment of his heart attack, while he was training for what sounds like a crazy bicycle hill-climbing challenge. Fortunately, he has now fully recovered, but I can’t help feeling that this might be a 10th principle: however exciting the job, don’t overdo it.

Oct 22, 2024 | Scholarly publishing

Towards the end of September, Peer Review Week hosted a whole host of content around the subject of peer review, its processes, and editorial policies, as well as highlighting updates and current threats to the system that underpins academic publishing.

Editage, in partnership with EASE, organised a discussion entitled “Envisioning a Hybrid Model of Peer Review: Integrating AI with reviewers, publishers, & authors”, led by Chris Leonard (Director of Strategy and Innovation, Cactus Communications). He was joined by Serge P.J.M. Horbach (Institute for Science in Society, Radboud University, Netherlands), Hasseb Irfanullah (independent consultant on environment, climate change, and research systems) and Marie E. McVeigh (Lead, Peer Review Operations and Publication Integrity, Mary Ann Liebert Inc).

The discussion started with highlighting problems with peer review today; noting that we are engaging with a mid-20th Century system of “gatekeeping” which has developed into one setting standards for research, a space to develop work and ideas, where communities can collaborate and a place to discuss what it means to create “good” standards. A major issue with the peer-review process, as highlighted by Serge, is finding quality reviewers – the number of invitations required has increased due to subject specificity and interdisciplinary fields overlapping. The volume and vast number of articles exacerbates this issue and small communities of interest can no longer support growing areas of academic research alone. This can lead to exclusivity and the network of reviewers within it is diminishing.

Hasseb raised the question of whether peer review has become overrated? If a manuscript’s decision can be made on the outcome of two reviewer reports – does this undermine the whole of the research? As peer review is not valued necessarily by the publisher in a financial sense, the value of its contribution is lost. However, it is important to understand that the communication around the research does not end with the peer-review process, it starts upon publication.

As the discussion progressed, the focus turned towards a hybrid approach to peer review and what that means. A hybrid approach could equate to a generative AI and human reviewer contributing towards a reviewer report, while the Journal Editor provides a final commentary. This assistance would provide “free labour” and generative AI is a good bibliographical research tool. Marie posed the suggestion that in cases such as this, it is ideal to allow machines to do what machines can do and allow humans to engage with the outcomes. For example, AI would be great at screening manuscripts, analysing citations and identifying peer groups. Such routine and rule-based tasks can be done quickly and efficiently. Evaluations can then be conducted by humans, who are able to decipher and assess whether the article adds to the scholarly record. As human reviewers cannot be located quickly enough, this dual aspect might be the quickest, cost-efficient way to support peer-review processes going forwards.

As journals look to lean on AI technologies, we need to understand what a journal is and what it does. Is it still simply a facet to share and disseminate work and ideas, or is it becoming more than that – a place where communities engage and develop their insights? By involving AI, do we consider it a peer? If community is at the core of journal publishing, surely humans will be required to keep that sense of togetherness ongoing. Without it, it’s just computers talking to each other.

May 9, 2024 | Scholarly publishing

The “text recycling in research writing” COPE Lightning Talk in April 2024 was presented by Professor Cary Moskovitz (Director of the Text Recycling Research Project at Duke University, NC, USA).

Text recycling can be defined a number of ways. Essentially it is the reuse of material – whether it is prose, visuals or equations – in a new document where material is used in the new document as it was in the original source. The material is not presented in the new document as a quotation and usually one author on the new document is the same as the original.

Recycling material in published papers is common, however authors do need to be mindful of the copyright law that they are submitting their paper under. Under US copyright law, authors may find that generally they can reuse portions of text under the Fair Use clause, and in many STEM journals publishers ensure their policies work to accommodate this, so as not to infringe the copyright/legal ownership.

The ethics of recycling are different and it requires appropriate transparency. Legalities and ethics may differ and the author must ensure that permission has been requested if their use of copyrighted material falls outside of the Fair Use guidance and journal policies. Text recycling should be done within best practice – we cannot expect authors and editors to be experts in copyright law, however publishers’ policies should adapt to and support their communities. It is also important to highlight that authors should check their publisher agreements as this is where the details lie. These will vary from publisher to publisher and the rules around text recycling are not always consistent.

It is recommended to authors that if they are using work which is previously published, a statement could be included in the paper to highlight this, and this would act in accordance with best practice. This will allow the reader to know that the work is not original, but it will also signpost accordingly.

Apr 2, 2024 | Scholarly publishing

The March 2024 COPE Forum began with a discussion on ‘ethical considerations around watchlists’, hosted by Daniel Kulp (Chair, COPE Council).

During the discussion, the benefits and potential risks associated with watchlists were explored from the position of both individuals and journals, as well as how publishers should use them. In principle, a watchlist could be used as a quality control tool; usually kept private as a measure of accountability. If, however, the list was exposed/leaked, the publisher’s trustworthiness and maker of transparency can be held to account.

It is important to note what is included on a watchlist – is information recorded about an individual, including personal data? Do COPE offer any guidance on what kind of criteria individuals should meet to be on a watchlist? And how can an individual defend themselves or “remove” themselves from a list? These were some of the key questions raised during the conversation regarding individual authors or account holders. The threat is much greater to be named and listed; as careers, research programs and scholarly publications can all be potentially be disputed/disrupted if this extremely sensitive information is exposed in the public domain.

At an individual level, abhorrent practices to circumnavigate peer-review processes could be observed through “flagging” an author’s account – for example, to collate information about suspicious activity. However individuals have a higher right to privacy and such lists need to be regulated or kept private within the publishing house. Academic publishing is witnessing a systematic effort to undermine peer review; the rise of papermills, reviewer cartels and bad actors exploiting the system often for financial gain mean that individuals should be aware of this and make due considerations during submission.

Sharing nefarious behaviours is important and if publishers share systematic problems regarding behaviour amongst one another, they can collectively disrupt the ways papermills and peer-review rings operate. COPE has guidance on how EICs can share information. However, how can we share this information more broadly? The STM Integrity Hub offers a duplicate submissions check across publishers, which could be a useful tool to manage misconduct. This is being developed and the STM Integrity Hub are exploring managing this in an ethical and legal way.

One of the biggest risks with watchlists posed at an individual level is that account holders are added incorrectly or without proper reason. This could be very detrimental to an individual in terms of their career and may also possibly be defamatory and could have legal ramifications. Watchlists must aim to be transparent but not give away details of what we are looking for. The risk is higher for individuals as it can directly impact future employment and ability to do research. Should there be mitigation circumstances for appeal for minor infractions? A similar name could be a risk, for example.

In the absence of an agreed decision amongst the industry on what should and shouldn’t be on a watchlist, the main risk appears to be a legal one. STM have already advised that the industry needs to be careful regarding the type of data which is shared. Legally underpinning this stage is crucial to ensure an individual’s privacy and GDPR-compliance is maintained. It was suggested that if private watchlists are maintained, legal counsel should be able to advise how to evoke sanctions or prevent someone from publishing. The publisher however must be mindful of any reputational damage or litigation brought against them.

If an individual finds themselves on a watchlist they do of course have the right to reply, to ensure that the process is fair and transparent and that they can defend themselves and their position. It was raised that it would be good practice to notify an individual that concerns have been identified, which will allow them to ask for an appeal. It is important to consider and understand what the watchlist represents.

As the risks increase and the systematic manipulation of peer review is attacked, the ways in which this data is captured in order to identify patterns of misconduct has to be carried out quickly, ethically and legally in order for the publisher to maintain integrity and be commercially viable as well as managing its own trustworthiness.

Mar 19, 2024 | Events, Scholarly publishing

On Tuesday 12th March we headed off to one of the industry’s leading events in academic publishing. This year the London Book Fair was buzzing; the main hall was filling up as soon as the doors opened, and the Tech Theatre and Main Stages had consistent queues. Meetings, networking and seminars are all key elements of the fair and this year we were lucky enough to participate and find out more about the challenges facing the industry.

On Tuesday 12th March we headed off to one of the industry’s leading events in academic publishing. This year the London Book Fair was buzzing; the main hall was filling up as soon as the doors opened, and the Tech Theatre and Main Stages had consistent queues. Meetings, networking and seminars are all key elements of the fair and this year we were lucky enough to participate and find out more about the challenges facing the industry.

The hot topic as ever was AI, and we attended a talk hosted by Sureshkumar Parandhaman (AVP of Publishing Solutions and Pre-Sales, Integra) entitled “Embracing AI in Publishing: Transform Editorial Excellence and Enhance Downstream Efficiency”. Needless to say it’s evident that tools are being developed to tackle many of the administrative tasks that editorial services provide, however we know there will still be an important role for us to play as integrity, quality and efficiency are all integral within our roles.

During a key discussion about AI and copyright it was stated that when King Charles’ recent surgery was announced, over 250 AI-generated texts filled the virtual Amazon bookshelves the very next day! Content is quick to make, and the session “Global Discussion of Machines, Humans, and the Law” hosted by Glenn Rollans (President and Publisher, Brush Education Inc.), Nicola Solomon (CEO, Society of Authors), Porter Anderson (Editor-in-Chief, Publishing Perspectives), Dan Conway (CEO, The Publishers Association UK) and Maria A. Pallante (President and CEO, Association of American Publishers) highlighted how important it is for the copyright holder to be accredited and financially rewarded. Whilst Government bodies manage policy and next steps with regards to AI, we need to be mindful of what we “feed” to LLMs and how “Fair Use” comes into play.

The Editorial Hub at LBF 2024

A panel discussion entitled “AI & Publishing – Navigating the Impact of Large Language Models” was hosted by Lucy McCarraher (Founder, Rethink Press Limited), Nadim Sadek (Founder & CEO, Shimmr AI Ltd), and Sara Lloyd (Group Communications Director & Global AI Lead, Pan Macmillan). The group discussed the ways that LLMs can spark creative thinking and should be used within workshops as a tool to support creativity. In terms of optimising the features of AI it was recommended that the industry looks to use it for creating the structural analysis needed for promotion work. An AI bot can extract book DNA far quicker than a pair of human eyes, so let’s use its skillset appropriately and it can enhance our work, rather than hinder progress. As well as creating copy, it can also be useful for generating advertising and images. As well as connecting couriers and customers, it can scroll databases to highlight potential consumers. The panel really encouraged the audience to engage with the features of AI bots and embrace how useful it can be to enhance and build on capabilities.

On Tuesday 12th March we headed off to one of the industry’s leading events in academic publishing. This year the London Book Fair was buzzing; the main hall was filling up as soon as the doors opened, and the Tech Theatre and Main Stages had consistent queues. Meetings, networking and seminars are all key elements of the fair and this year we were lucky enough to participate and find out more about the challenges facing the industry.

On Tuesday 12th March we headed off to one of the industry’s leading events in academic publishing. This year the London Book Fair was buzzing; the main hall was filling up as soon as the doors opened, and the Tech Theatre and Main Stages had consistent queues. Meetings, networking and seminars are all key elements of the fair and this year we were lucky enough to participate and find out more about the challenges facing the industry.